Elisha G. Selchow began his career as the young inheritor of a failing box factory founded by his German-immigrant father. Underage and in debt, he was unable to secure traditional lines of bank credit to stock his factory, but in a surprisingly cunning move borrowed on a cache of goodwill left by his father, securing small loans from neighboring businessmen in $100 and $150 amounts. Capital assured, he was able to rebuild his father's company, with one agent recording in 1864 that he was a "correct, reliable, industrious young man, underage, prompt in his payments and doing well." In 1867, Elisha found his first success in late 1870 by capitalizing on the fortuitous failing of Albert Swift's gaming firm, for whom he had produced boxes. That company's impending bankruptcy allowed Elisha to purchase publishing rights to the already popular parlor game, Parcheesi, and maintain ownership of this lucrative property throughout most of his company's long existence.

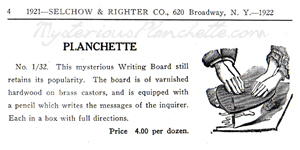

While Selchow & Righter planchette labels claim the firm manufactured the devices "since 1860," there is much cause to doubt these claims, and it was most likely a move to avoid any sort of claim of patent or trademark infringement in the wake of the First Great Craze. The company's earliest planchette ad dates from 1889.

The firm would not even officially take the name Selchow & Righter until 1880, when Elisha formerly partnered with another increasingly valuable asset he had acquired from the dissolution of Swift's company -a talented clerk and manager named John H. Righter. By this time, the company had combined their box factory and gaming concerns under one roof, and were able to facilitate the manufacture and wholesaling of their own in-house product; typically repackaged imports and factory-produced goods purchased in bulk. They also streamlined distribution of their own product as well as the toys and games of their competitors through a network of trunk-toting salesmen known as "drummers." In this way, distribution of their products spread far and wide. Additionally, their ads began to appear in various media formats in beautifully-lithographed ads, including their aforementioned 1889 "Scientific Planchette"solicitations.

Thus was the life of corporate "jobbers" in the gaming industry -a trait common to many firms that produced planchettes in a time before toy makers took the offensive on trademark and patent infringement. In this way, Selchow & Righter primarily made its money through the manufacture and distribution of other firm's games, in whole or in part, acting at various stages as printer and lithographers for other companies, manufacturers of components of smaller sets for competitors like Milton Bradley, or licensing out the intellectual property of other firms and rebranding it under their own wholesale banner.

Thought this pattern of business continued up to and beyond the deaths of the founders of Selchow & Righter (1915 and 1909, respectively), by the 1920s the business expanded into true manufacturing. They even experienced another Renaissance in the 1950s with the massive popularity of Scrabble and again with Trivial Pursuit, but failure to properly gauge the overbearing popularity of a rise of electronic games in the 1970s led to a steady decline in the company's fortunes, and Selchow & Righter, long a privately-held company, changed corporate ownership several times before finally selling to Hasbro in 1989.

An unusually long period of production makes Selchow & Righter's "Scientific Planchette" among the most commonly-encountered American planchettes. Their nearly-identical form to E.I.H's Scientific Planchette makes it likely that either both companies acquired the product from a shared manufacturer, rebranding it through their own labels, or, equally as likely, the planchettes were actually produced by Selchow & Righter, which seemed to have little compunction in producing products in whole or in part for other firms. It seems unlikely that either firm would have been comfortable with such an arrangements, given both firms' reputations as jobbers in the industry, and the commonality of the practice in that early era.

Like their E.I.H cousins, Selchow & Righter planchettes are fantastic, quality specimens. They possess a classic "shield" shape cut from 3-ply maple, with nicely rounded edges. The planks are of a good weight and large size, measuring just over 8-inches long from their scalloped backs to their pointed noses. They are drilled with a simple pencil hole, and complete specimens have a brass tube and grommet-shaped rim serving as a pencil retainer firmly snugged in place, typically the first piece lost on these items. While the proper orientation for this insert is to have the tube protruding topside, this is also counterproductive during the board's operation, when nothing but friction, rather than the flared rim, retain the piece in place. For this reason, most surviving examples are discovered with this insert inverted, though it is easily rectified with careful removal and replacement, assuming it hasn't fallen out of its own accord.

The castors are of middling quality, not quite the flimsy, wobbly legs of the British Manufacture boards, but certainly not up to the standards of the cast Bangs Williams or Kirby & Co. boards. They thankfully screw into the base of the board directly, without nails, and only of a depth as to not break through the board's top plane. While the castor stems and wheel retainers are more sturdy than others like them, the wheels are unfortunately quite wobbly, and vary from a basic basewood (both natural and red-stained specimens have been observed) to a brown Bakelite material that could just as easily be recycled buttons. All are held in place with simple bent finishing nails.

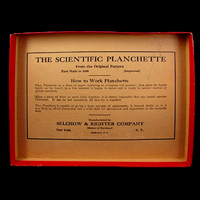

The Selchow & Righter boxes are among the finest examples among all planchettes, particularly in later years, which is fitting given the company's origins as a box manufacturer. The earliest versions are thick and durable, and feature nice, elaborate font styles, beautifully bordered and accented script-work, and a prominent woodcut of the hands of two users guiding a planchette toward some spirit's scrambled, illegible message. The outer labels are usually found in a pale green or light blue, though earlier examples are printed on dark red paper. The interior of the boxes often carry a label repeating the instructions found pasted to the board's underside, along with clear indication of the manufacturer as Selchow & Righter, unlike the E.I.H. planks, which have identical labels, but do not carry any such identifying mark; an easy tell for specimens since separated from their boxes. Like many other makes of planchette, they are also marked "improved," though since all known examples all say "improved," it is unclear just what earlier form they might have improved upon!

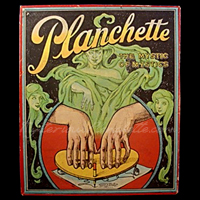

The later boxes most likely date from the factory expansion of the 1920s, at the very earliest. The boards remain unchanged and of the same appearance and quality, but the boxes undergo a metamorphosis into the most beautiful gaming packages ever produced. Gone is the monotone black print on a single color label, replaced with a full-color lithograph of a trio of ghostly, shrouded spirits printed in an eerie green. A new tagline labels the content as "The Mystic of Mystics," and the accompanying "mystical" spirits guide a pictured planchette user's hands over paper. The scribbled message has not become any more recognizable with time, but the lack of that small detail can be forgiven in the face of such a fanciful and artistic package.