Planchettes, dial plates, and talking boards evolved during the latter-half of the 19th-century, at a time when age-old religious notions found challenge in sweeping scientific discoveries and industrial advancements that rocked the firm footholds of faith. A public primed by decades of charismatic mesmerists, psychic healers, animal magnetists, and phrenologists plunged headlong into new religious territory when the young Fox Sisters claimed communion with spirits through the mysterious raps heard in their Hydesville, New York home in early 1848. With the veil between the living and the dead seemingly parted, the belief in and experimentation with spirit communications spread at a rate previously unseen at the time, aided by advances in telegraph technology and an unprecedented cooperative media. A grand new age of both science and religion were at hand, one that would find them again at the greatest odds, but also with a common enemy that threatened the sanctity of both.

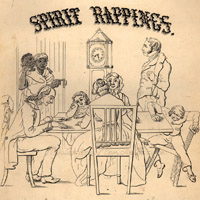

Against this backdrop, homegrown spiritual experimentation became the most popular of parlor pastimes. Table-tipping was all the rage, as participants could now spread their outstretched hands on top of the nearest piano stool or dinette, and likely experience mysterious raps, unexplained tilting, and other strange movements as the tables exhibited seemingly intelligence responses to questions. The popularity of the pastime was addictive and spread rapidly. By 1851, one Philadelphia observer reported that some 50 or 60 séance circles had been formed in the city, and a Cincinnati newspaper editor estimated more than 1,200 mediums operating in his city alone. Even those along the western frontier were hooked, and in 1853, another journalist remarked that, "it was not by any means unusual on entering a log cabin to find the good, simple people seated around the rude table upon which the raps were being made." Table-tipping and spirit rapping soon reached England and spread to the Continent, and on both sides of the Atlantic, inventive new ways to communicate with the "so-called dead" were imagined and made reality.

With the establishment of the belief in spirits willing and able to communicate with the living through special gifted mediums, it was only a matter of time before improvements were made to the manner of communication. Simple knocked affirmations to often leading questions quickly gave way to ponderous alphabet-calling, wherein the raps would select letters from a called-out alphabet in order to spell out messages one letter at a time. But accounts from even the earliest days of rapping mediums tell of alphabet cards and tiles used to facilitate faster communication. Given such close antecedents to the classic talking board form, and the fervor with which inventors pursued devices to exploit this growing craze, it is somewhat amazing that the aspiring spiritual consultant would have to wait 40 years for the first commercial realization of this earliest form of alphabetic communication in the form of Kennard's Ouija board. Instead, alternate routes were taken, perhaps because the proliferation of popular alphabet-learning cards and alphabet boxes full of lettered tiles were commonplace learning tools for children and readily at hand for impromptu seances. Whatever the case may be, long before talking boards ruled the roost, the planchette stole the hearts and minds of the newly-necromantic public.

French and German cultures were particularly primed to accept the leap of faith from their popular belief in Mesmerism to spiritual communion. In fact, despite the collector's viewpoint of planchettes being a uniquely American and British phenomenon, it is in France that devices not only get their name, but originate. We are lucky enough to have a birthdate for these first devices as well. June 10, 1853 marks the first known use of an impromptu automatic writer in the West, as witnessed by the Spiritist Allan Kardec, who attended the Paris table-tipping seance at which its invention occurred. According to Kardec, a "fervent partisan of the new phenomena" present at the seance made the suggestion as an alternative to the laborious process of alphabet-calling and tiresome rapped responses, and manufactured a small upturned basket, to which he secured a pencil, in order for several participants to participate in writing out messages from their spiritual controls. The device's first message said sternly "I expressly forbid your repeating to anyone what I have just told you. The next time I write, I shall do it better." No one now knows exactly who coined the phrase, but the name "little plank" was given to the device, or, in the original French, "planchette." It wasn't the first time spirits had seized a host in order to write messages, as Isaac Post, associate of the Fox Sisters, had done so years previously with automatic writing. But the planchette offered for the first time a cooperative session with multiple sitters, opening up intriguing new possibilities for aspiring spirit communicators. And the idea soon spread.

Other accounts of the planchette's discovery differ somewhat, though they lack Kardec's reliable firsthand narrative. G.W. Cottrell, who would later be responsible for manufacturing America's first planchettes, claimed in his 1868 book that a sect of French monks was responsible for developing planchette writing techniques in a Parisian monastery. According to Cottrell, the process of their spirit writing was witnessed by the nephew of the Bishop of Paris, who then introduced it to the seance scene in Paris, which may not directly contradict Kardec's own account, and, in fact, may identify the same "fervent partisan" Kardec references. We do know that by the end of 1853, a pastoral letter written by the Bishop of Viviers was railing against the use of the planchette by the clergy. Whether the planchette's true origins migrated from the monasteries to the seance parlor, or vice-versa, we may never know, but there is no doubt that the device is a uniquely French.

The use of planchettes spread quickly across Paris, no doubt enhanced by the enticing and often sexually-charged idea of cooperative spirit communion, with men and women sitting in close contact, often in low-light, their hands intimately touching the board as they wrote out spirit messages. By the end of 1853, a small cottage industry willing to provide this new tool took root in France and England, with sympathetic surgical equipment and scientific instrument makers such as Thomas Welton and Elliot Brothers providing the devices on a small scale. Even then, planchettes still remain somewhat exclusive to Spiritualists during this time, and we have only the barest snippets of news of the device for several intervening years. They had yet to ignite the passionate fires of popular culture.

Meanwhile, other spirit communication devices had their time in the limelight, all briefly flaring before fading into obscurity. John Rutter experimented with animal magnetism with his Magnetoscope, a pendulum device similar to later divination instruments. Isaac Pease of Thompsonville, Connecticut was the first American to manufacture a spirit communication device, and in doing so produced the first "dial plate" boards with his invention of a clock-like dial face with an alphabet-lined circumference and assorted radial messages that spelled out messages by means of a manipulated index that pointed to selected letters when manipulated by a medium. Famous chemist Dr. Robert Hare, too, constructed similar devices of his own, and modified some of Pease's dial plates to create foolproof machines meant to disprove spirit communication, but the aging professor only succeeded in convincing himself of the truth of the tested medium's claims.

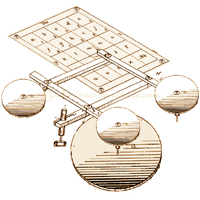

In 1854, Adolphus Theodore Wagner submitted his patent for a spirit communication device, which he called the "Psychograph" or "Thought Indicator." This complicated tool worked something like a draftman's pantograph, with several sliding levered arms controlled by multiple sitters who placed their hands on wooden disks to manipulate the device, thus pointing out letters and numbers on an octavo-sized alphabet card. It was an incredibly complicated affair-not unlike a writing pentagraph, only with the additional disks and even a glass plate to facilitate the sliding action-but with this invention, we have not only the world's first patented planchette, but also the world's first talking board patent!

The year 1858 marks a faithful milestone for spirit communication devices. Like most accounts for the era, there are slight discrepancies and contradictions, but we do know that in that year, the planchette crossed the Atlantic into America. At this time, prominent Spiritualist, legislator, and social reformer Robert Dale Owen traveled to Paris, then London, then finally back to America, accompanied by his companion Dr. H. F. Gardner, himself a well-known Boston Spiritualist and paranormal investigator. Gardner's account, as related by his friend and planchette manufacturer G.W. Cottrell, later recounted in a letter dated May 5, 1859:

"In Paris, I witnessed a method of communication of which I had not heard in America. The instrument used by them they call a 'Planchette.' The method of communication is by writing...I called upon the manufacturers of the above-mentioned instrument to purchase one to take home with me, and he informed Mr. Owen, who was with me, that he had made and sold several hundred in Paris alone "

Another account comes from planchette maker Thomas Welton, who has a slightly different version of the pair's trip and subsequent import of planchettes to American shores. He recounts that during the same 1858 trip, in London just before their return to Boston, Mr. Owen received a written planchette communication given to him by an acquaintance, who had been instructed in writing to "Go to my son and tell him that I will be with him this day and month, to cause him to make such alterations as I wish in the book he is now writing, ";Rt. Owen." When shown the message, Mr. Owen claimed it was not only from his own recently-deceased father, but also in his father's handwriting, and about a book project previously kept strictly confidential. So impressed was the younger (and still living) Robert Owen, claims Welton, that he purchased six of the devices and returned to Boston with them. Whether they were purchased from Welton is unknown, though it may decipher the contradictions of American versus British forms to be found in the 1867 "Once a Week" article.

Whether Gardner or Owen is responsible for the device's import to America hardly matters. What is important was that upon their return to Boston, the bookseller G.W. Cottrell had 50 copies made of a specimen provided him, which he made available for sale in his stationary store at 36 Cornhill Street beginning in 1860. They apparently did not immediately catch on. One writer later remarked these early copies were "like the modern planchettes, though not so elegant in appearance"-undoubtedly a reference to the more intriguing lines and sweeping cutaway of the Kirby & Co. planchette, which dominated the market at the time of the writing. Perhaps they were not heart-shaped, but rather of Welton's distinctly British form, with a flat back and round nose. We may never know, but hold out hope for new discoveries.

But here, too, the popularity of planchettes stalled. The immense distractions of the American Civil War took over the public consciousness, and spiritual experimentation began slowly evolving from its innocent parlor-pastime days into the more unified religion of Modern Spiritualism, with all the polarization and resentment a break-away sect can solicit. Media attention shifted to the more serious news of the war, even as seances became more sensational, with the rise of superstar mediums, physical manifestations, and spirit voices. But the planchette was waiting in the wings for its turn in the spotlight, and the curtains soon began to part to usher in the First Great Craze.